Detecting violence is easy because it is transparent, we know and feel it when we see it, but locating the origins of violence (the why always covertly peeking behind the act) is an impossible gesture. We can look to psychology for their answer: violence emerges from the mentally ill—one must be mentally unstable to commit a seriously violent, atrocious act. This, of course, resolves the question of evil—it is drained of any serious content. We are all absolved, since it isn’t our actions, it is, instead, our brain’s mis-action—violence is merely the expression of a certain configuration of hormones, brain chemicals, and neurological pathways. Xanax, or lithium, becomes the cure for evil.

Similarly, we could turn to sociology: violence emerges from socio-economic conditions and certain cultural factors. This, again, absolves us of the issue of evil and the individual’s place within it. Violence becomes nothing but a certain misconfiguration of the social.

We all know, though, that these deterministic prisms are insufficient—they miss something essential about violence. School shootings—or any mass shootings—are not accepted as purely sociological or psychological events.

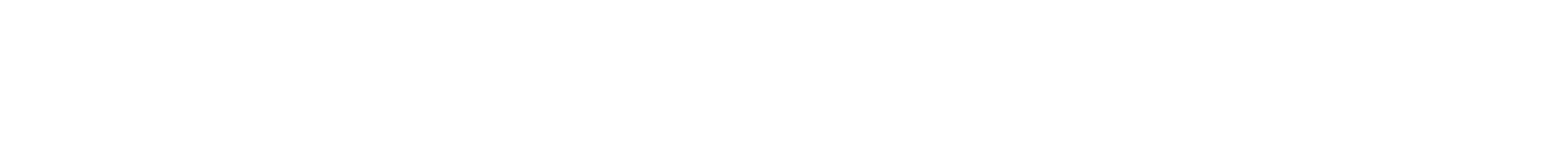

In New Millennium Boyz, Alex Kazemi’s debut novel, violence does not beget violence and is not merely rooted in poverty or mental illness; rather, boredom—and the desire to exceed banality and reach some kind of fame (or anti-fame)—begets violence. Violence, even evil, comes from a happy family and television and a lack of material concern. There is something true here that we’ve all seen and felt: the contemporary turn—modernity—brought with it a new mode of violence, of which mass shootings are visibly indicative.

NMB is a screenplay-esque account of a teenager, Brad Sela, living in an unnamed town. The novel catalogs violence that Brad both inflicts and suffers (bullying, killing an animal in a satanic ritual, taunting and denigrating women & minorities, himself being humiliated and even sexually assaulted) and the inner tension between what he is doing and who he wants to be, all during his senior year of high school at the start of the new millennium.

The novel isn’t (just) about school shooters, yet they haunt the story. Before his first day of school after an idyllic stay at summer camp, Brad complains about his new clear backpack and his mom tells him: “You have to think about what this feels like for me. The country feels different now.” Columbine is always looming, menacingly, in the background of the text.

At school, after a transformative and introspective summer, Brad sheds his old friends and makes new friends, Shane and Lusifer (Lu for short), who are the prototypical school shooters: loners, equally narcissistic, sadistic, and depressed. Shane and Lu’s relationship uncannily mirrors Dylan and Eric—one is the more active, sadistic figure, and the other seems to be a passive, depressed follower. The only person Lu (the sadistic one) worships more than the Columbine shooters is Marilyn Manson.

Formally, the book is dialogue-centric: it is almost entirely devoid of description or notable stylization. The subdued prose is very readable, and more than occasionally the spare-barren style contributes to moments that realistically mimic the 2000s teen’s non-censored, pre-politically correct (and at times, blatantly racist) speech. (“Have you ever noticed if you say Adidas in a spic accent, it sounds like ‘adios’?” “Adidos, adidos, adidos.” “Fucked. That’s so fucking sick.”)

The prose does, though, quickly become insipid, almost flaccid. Kazemi writes the book according to the tonality of teenage angst: informed by slang, at times boring, and other times overly-emotionally charged. Yet, this is knowingly deliberate; Kazemi doesn’t seem to be interested in becoming a prose stylist.

As the narrative sprawls forward, the prose’s purpose begins to obfuscate the deeper premise, and it becomes unclear if the incessant references to time-specific (Y2K) celebrities and shows and movies and music and products are satire or attempts to set the cultural-historical scene—it reads like a novel unsure of where to direct its ironic gestures. This is complicated by the fact that each end of the spectrum (saturating the text in brand references either as satire or as a genuine attempt to establish the cultural milieu) is vaguely unpleasant to read and already-tread territory. It is satire, but it is oftentimes difficult to discern the subject of satirization and its function.

It is uncertain, for instance, if the characters are mimicking actual teenage speech or are meant to mimic the faux-realism of television shows and movies about teenagers; it seems, at times, to have authentic fidelity to slang and other times to have a sartorial distance, mediated by other inauthentic representations of the early 2000s. Finding the threshold of ironic satire and actual sentiment is nearly impossible.

Confusingly, there are abrupt moments of pure sincerity from marginalized characters that are essentially didactical. One female character explains to Brad that he is apathetic to women’s issues because he is a straight, white male. Another gay character explains the violence that he and others experience. These blindingly unsubtle moments puncture the polymorphous satire and nuanced, accurate depiction of teenage angst; it becomes increasingly obvious that these moments are meant to tell us where the book really stands on social issues. It isn’t that these didactic interventions are factually or morally wrong, but rather that they undermine the things that the novel does well—depicting the utter moral confusion of adolescence.

The formal inconsistencies (or, at least, confusions) betray its narrative incongruities: Is this a book making fun of satanic panic? Or one that sincerely believes in it? Should we take the main character’s (and his friends’) acts of violence as a warning or as dismissive satire? Is NMB telling us that school shooters are overwhelmingly white males due to them being the pinnacle of white privilege?

One cannot deny NMB’s basic insight: there is a boy-crisis that has culminated in the phenomena of violence like school shootings. There is something to the suburban-boy syndrome and the anti-vitality of the suburbs, and the media is complicit in the schizophrenic image of what it means to be a boy.

The novel shows the commercial media’s conspicuous insistence on fame, glamor, and enjoyment—and we find a boy at an intersection where fame and adventure and libidinal exertion are celebrated above all yet who lives in the absence of all three. Brad is confronting expectations and a life that seems void of life itself.

A kernel of truth appears in the novel’s recurring idea that a certain kind of violence comes from banality—a sort of suburban-boy syndrome. Bound up in this is a rejection of conformity that erects its own conformity. As Brad continues with Shane and Lu, they develop fidelity to abjection: the only things that are tolerable are that which is intolerable to straight suburban society.

Nothing is farther from a family with the white-picket fence, dog, and television than a school shooting—a response to normalcy from the very outer rings of depravity. Something that, counterintuitively, only makes sense as a modern modality of evil that is spurred not by need or power or belief or some Cause but rather by senselessness and the desire to be known in the media landscape where being known is truly being.

This emptiness plays out in their fantasies and obsessions: Brad, Lu, and Shane’s lives are dominated by media identification. These boys define themselves by what music, celebrities, and other cultural landmarks they like as much as they define themselves according to what they dislike.

Brad is asking himself who he is and who he will be, and the responses mimetically bounce off those around him; his parents tell him he is a “good boy” while Lu tells him he is, in his heart, the very opposite, and the media concurrently implores him to fetishistically drain enjoyment and pleasure out of every second of life.

NMB’s crux is found here, caught between the multiplicity of responses. As the reader can see (and, as Sartre would remind us with his maxim, “existence precedes essence”) Brad is what he does. Lu and others are trying to convince him what he is determines how he acts. In Brad’s school shooter behavior and complicities in others (mainly Lu’s) actions is the simple grappling in the dark that one performs during the transition from childhood to adulthood: sex, drugs, love, and confronting the unknown of the future. Brad seems to be an expression of a transitory (universal) stage in development (from childhood to adulthood) that happens to be taking place during a particular stage in history—among the initial proliferation of the internet and e-pornography and affluent middle-class suburban boredom at the new millennium.

For America, this collision of post-pubescent boys and modernity has been abysmal. Modernity’s fundamental loss of something reverberates through America’s boys in NBM like a sub-audible hum that no one can hear until it is already catastrophically loud.

It still isn’t clear who or what exactly to blame, with the finger pointing in every direction, yet the novel, in a slightly clumsy manner, gives glimpses of those areas of American life to help us understand what has gone wrong.

By the end, Brad Sela does not end up a school shooter—but he doesn’t prevent one either.