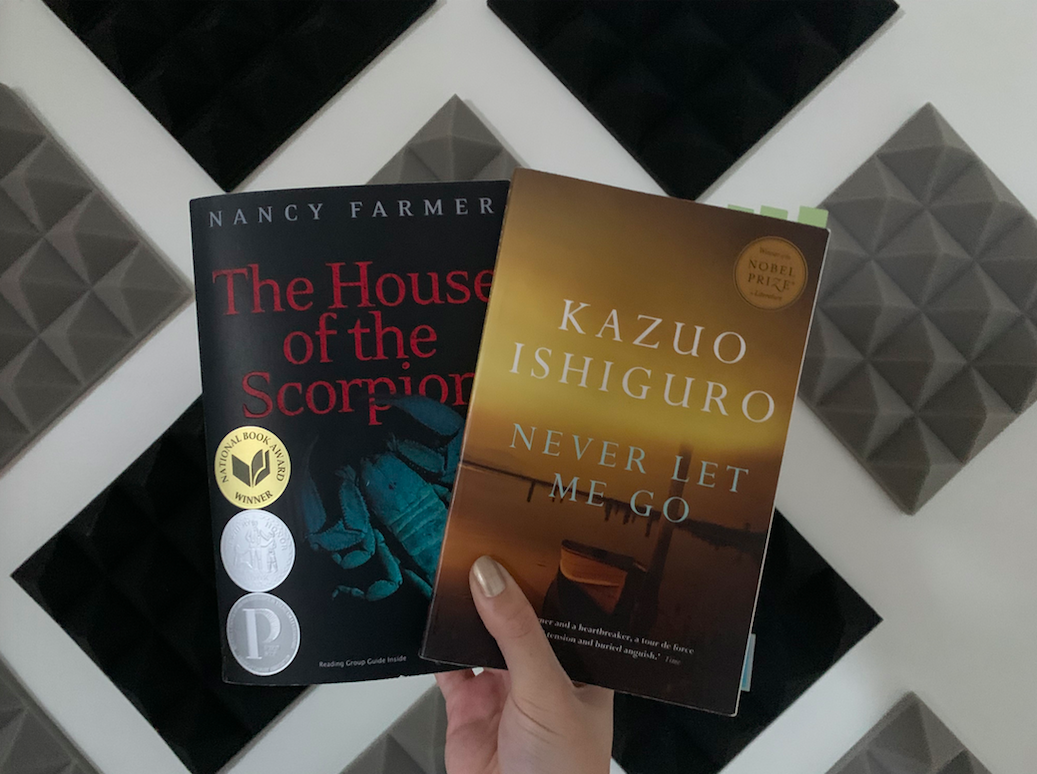

Never Let Me Go & The House of the Scorpion

The work of Nancy Farmer and Kazuo Ishiguro, The House of the Scorpion (2002) and Never Let Me Go (2005) respectively, were published only three years apart; however, these two novels offer two very different narratives, but share similarities in the themes they tackle and the expansive timeline that the story takes place over. With the rapid advancement of biotechnology, the two authors question what it means to be human. Given the complexity of the question at hand, readers can safely assume that this comparison will be much longer than the others. And though these two works though not unexpectedly placed together, individually, they offer powerful messages on the concept of clones and cloning.

From childhood to adolescence, The House of the Scorpion follows the narrative of the protagonist, Matteo “Matt” Alacrán—the clone of El Patrón, and his turbulent childhood in the Alacrán household as he attempts to navigate among humans given his despised status. In the country of Opium that sits between Aztlán and the United States, clones are abominations of nature and Matt accepts that even though he appears human, he does not differ from an animal. Yet, through the compassion of supporting characters—María, Celia, and Tam Lin—Matt slowly comes to realize what it means to be human.

From childhood to adulthood, Never Let Me Go centers on the story of Kathy, her life at Hailsham, and her relationship with her friends, Ruth and Tommy. The Hailsham offers its students ‘fulfilling’ childhoods before informing the clones of their true purpose and identity—clones destined for a life of organ donations. However, before reaching adulthood, Kathy and her friends discover the truth and question what it means to be human, but in a way that differs from Matt in The House of the Scorpion.

In The House of the Scorpion, Farmer emphasizes themes concerning the freedom of choice and those who control it, dehumanization, nature versus nurture, and the humanity of the naïve and also those who are often overlooked. For those living in Opium, El Patrón controls both clones and people through authoritarian rule, whether through fear or forceful implants that render victims mindless. In Aztlán, Farmer illustrates a different form of control: brainwashing.

In terms of dehumanization, in the novel, all those within the Alacrán household consider Matt an animal. They emphasize how, although he is the clone of a powerful drug lord, because an animal birthed him, he is also an animal himself. Matt internalizes his label, and although he consistently tries to challenge it throughout the novel. Matt frequently compares himself to El Patrón, someone he should be like and often tries to be like but is ultimately different from. He describes himself as “only a photograph of a human”, an imitation rather than the original. Yet, Matt seems very different from El Patrón and seems to be capable of greater levels of compassion and understanding.

Matt’s challenge towards the labels attached to his clone identity comprises constantly trying to prove his humanity and difference from other clones through his upbringing, intelligence, education, and musical talent—the thing he has which El Patrón never did. Yet, all these things do not matter to El Patrón. El Patrón views Matt’s education as a mercy; he offers his clones a childhood that he never had, before the clones donate their organs, much like in Never Let Me Go, to keep El Patrón alive. It seems Matt is in a constant battle against what others believe he is and what he desires others to see him as. Opium’s normalization of the animalization of clones plants the idea within Matt that no matter how similar he is to other people, others still do not see him as ‘human’. However, even though the Alacrán household treats Matt unfairly, Celia, Tam Lin, and María—his only allies—recognize the humanity within Matt, regardless of his clone identity. Those with the most compassion and empathy seem to be the ones most overlooked in Opium’s authoritarian society.

Ultimately, the only marker of difference between Matt and other ‘humans’ is a label stamped on the bottom of his foot.

In Never Let Me Go, Ishiguro offers a very different concept of what it means to be human. Hailsham not only aims to offer ‘fulfilling’ childhoods to clones destined for a life of organ donations. However, the directors of the institution seem to have the aim of emphasizing the humanity of clones through the art that clones create and their creativity to show that clones also have consciousness, dreams, desires, and emotion like other humans. Unlike Farmer’s novel, the society in Never Let Me Go does not view clones as monstrous, but rather, as pitiful ‘projects’ catered for the greater good of the rest of the population.

Furthermore, the clones in Never Let Me Go are modelled after individuals traditionally looked down upon by society, such as criminals, rather than powerful figures such as El Patrón in Farmer’s novel. Kathy’s society uses the modelling of clones after figures that are social outcasts to overlook the unethical and immoral practices of science. The novel emphasizes how the lives saved by the donations from clones, and the appeal of the implications of the presence of clone, makes it difficult for most to admit to the humanity of clones.

Like Matt, the characters struggle against their fate and try to challenge the direction of their lives, but their efforts are futile because the rest of society does not want to give up the solution that clones offer.

Both Farmer and Ishiguro’s novel presents a powerful message concerning the ethics of cloning and the immorality of science, as selfish individuals try to justify the murder of clones for the ‘greater good’ of the rest of society, ignoring the evidence of humanity that clones have. Even in attempts to offer clones a ‘fulfilling’ childhood and adolescence both as supposed mercy but also seems like an attempt at repayment, the authors show how robbing the lives of clones is the same as murdering ‘real’ humans. The message that The House of the Scorpion and Never Let Me Go leaves us with is that denying the humanity of clones does not make them any less human, and any life is worth far more than immoral solutions.