I hate Surrealism. I find it tedious, humorless, and hopelessly indebted to Sigmund Freud—a man who did as much to obscure and confuse the inner workings of human behavior as he did to uncover and explain it. The worst Surrealist artists traffic in airless, stillborn imagery that’s desperate to appear pregnant with meaning without ever earning it. They like to shock, confusing the effect with depth. Hans Bellmer (1902-1975) was a prime example of this tendency with his deformed sex dolls. These days the type of perversion he was into is served without a second glance by dozens of porn sites and myriad escort services. No need to inflict mediocre art on others to scratch the itch.

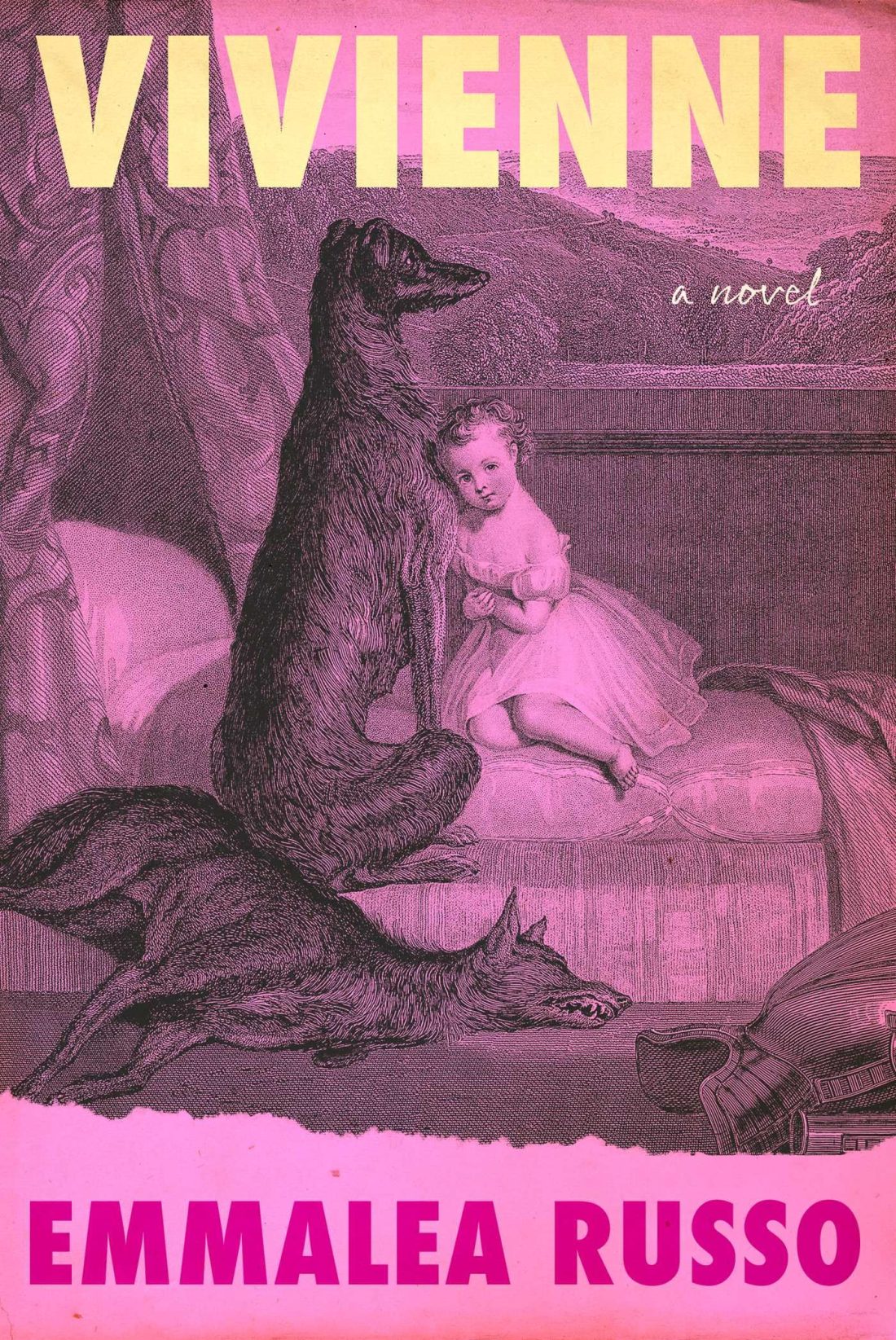

I say all this to make plain that I was prejudiced against Emmalea Russo’s hilarious, compulsively readable novel before opening the first page. But after just a few paragraphs it wouldn’t let me go. I’m not the type of reader who needs to like or identify with anyone I read about. What I demand is a distinct voice and the sense that the writer knows and loves her characters. As hateful, selfish, obtuse, or contrarian as Vivienne, Velour, Vesta, and Lars—the main players of the book—are, there’s not a single sentence in which I doubted Russo’s love and knowledge of them.

The historical Bellmer had a wife called Unica Zorn who committed suicide. Russo imagines a younger girlfriend for him, named Vivienne Volker, who may or may not have played a part in the wife’s (here renamed Wilma Lang) demise. Vivienne is an artist who quit practicing decades ago and now lives a quiet life in a shambling old house in Pennsylvania with her daughter and granddaughter. When a museum reaches out to include her work in a survey of forgotten female Surrealists, then cancels her participation due to rumors of her involvement with Bellmer’s wife’s death, the three women’s quiet life is shattered beyond repair.

Summarizing the events in the book does no justice to the joy of reading it. As I said at the top, the setting and themes don’t appeal to me in the least, but I burned through these pages in two or three days. The seamless way Russo alternates chapters from the point of view of the three women and one man with the deathscroll of performative social media outrage moves the story along so buoyantly that I was never irritated by characters, who, in almost any other context, would be unbearable.

Lars, the self-obsessed American Psycho-type gallerist, is especially familiar to me from decades of involvement in the art racket. As badly as I wished for him to come to a bad end, the graceful coda Russo gifts him made me wish I myself could be more generous. The book is that way throughout, zigging when I expected it to zag, rewarding when I was predicting denial.

Books about artists, especially ones about whom there is substantial documentation, are a tricky proposition. Inserting fictional characters into historical events risks a disjointed or difficult-to-believe narrative. Russo melds the real and imagined so well that I didn’t question the parameters of the world she created for a moment. Not the little girl in a romantic relationship with a dog, not a horrific utopian art project in which elderly women in comas give birth to new children, not the tiresome Surrealists or their sycophantic followers, not any of it.