It has become a commonplace to bash the preeminent poet Carolyn Forché for allegedly trauma-seeking, risk-averse poetic practice, especially after her second collection The Country Between Us became a runaway bestseller in the early eighties, and one of the bestselling poetry collections in the nation’s history at the time. Her collection, transcription, advocacy, translating, and preservation of what she famously termed the “Poetry of Witness” has established her reputation but at the same time provided such a double-edged sword that she needed to release an equally good memoir as a sort of rebuttal.

It was not as if her place in the poetic canon was disputed, but more so that a dispute had arisen as to how much one can truly amass and provide stories for other sentient human beings. Way more often than not, however, in her poetry, Forché does it correctly, sensitively. She seems to know that if it’s not your experience, it requires a great deal of care and craft to split the difference, which lesser poets see as a gaping black hole from which no personality escapes.

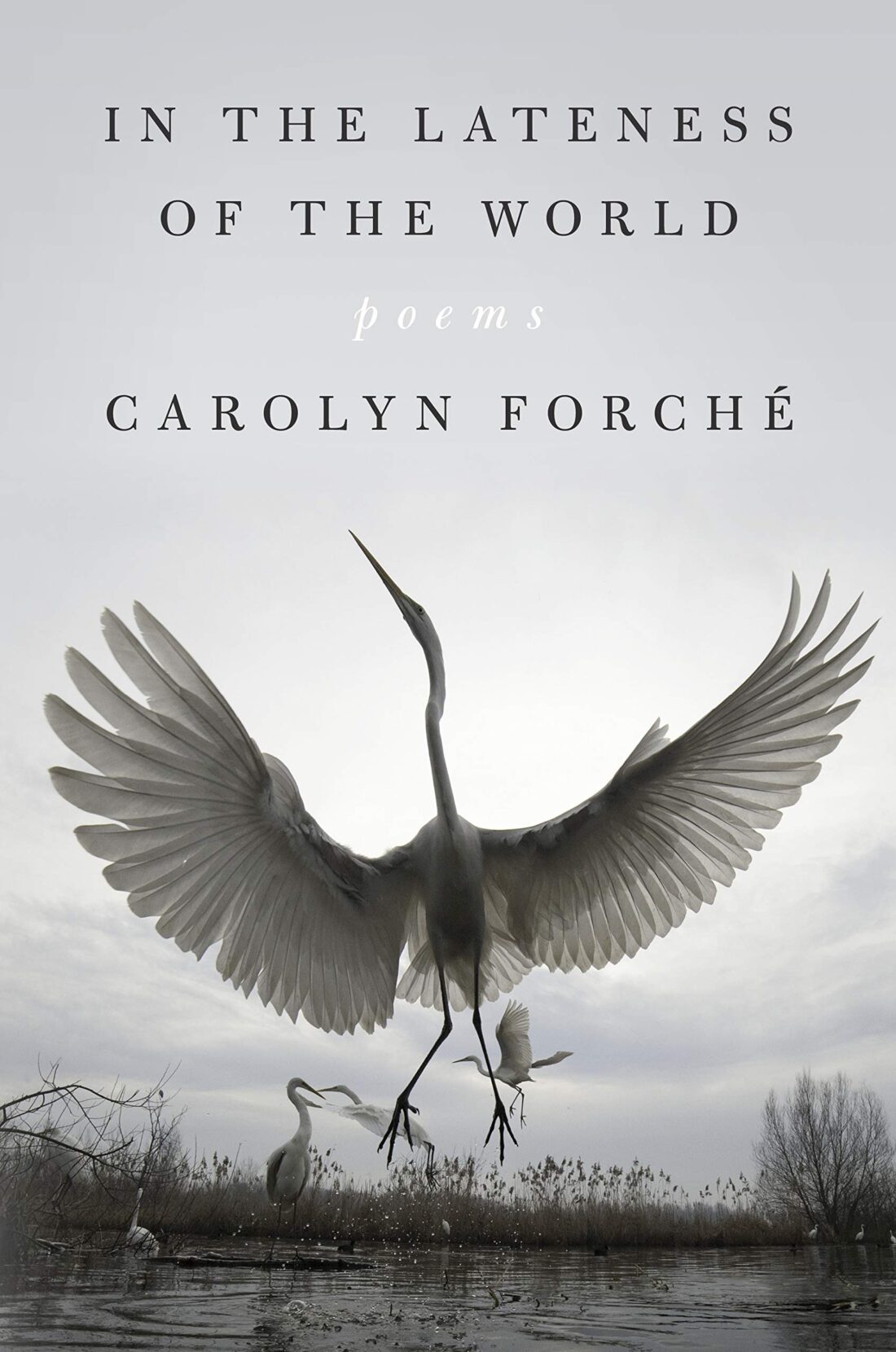

Forché does not write good poetry by virtue of researching the hell out of, and attempting to non-vicariously experience, her subject matter – all that is simply because she started out independently, self-taught. She is a good poet because of her technique, an attention to poetic craft that bleeds through the edges of her newest collection In the Lateness of the World in the most emotionally resonant ways since her stunning debut Gathering the Tribes.

Which is all to say that it’s a relief to see Forché firing on all cylinders, free to deploy her vast knowledge and technique as she sees fit. Both seem to be in service of a poem’s situationally momentous notice, and not a moment is wasted in the collection as it spurs itself through heightened elegy and then world-defeating (yet not defeatist) technical brilliance.

Since Milton’s “Lycidas”, the desire to impute oneself into an elegy has allowed self-expression and mourning to commingle equally in even the most well-meaning elegies. The best recent elegies, however, prove that knowing this inherent formal tendency is more than half the battle. This self-awareness imbues In the Lateness of the World—through its speaker’s placement—at almost all times in a directly embodied space they walk around in, live within, and mourn inside of. Many of the poems in the book are dedicated to friends of Forché’s that have passed away, friends who dedicated their lives to either poetry or culture, but always to the world at large. And it’s here that the Forché’s natural tendency to thrust herself into situations is able to take root and thrive—precisely because the elegy is an outlet that disguises its own necessity as an outlet.

One of my favorite aspects of the collection is the fact that many of the elegies that comprise the first half of the book are only quasi-sequences. They are successive poems that take on meaning as the poems accrue generally, in a haunting space – as if the reader is Dorothy staring out the window of her farmhouse at a whirling tornado, through which memories and poetic technique whisk along. But, unlike that story, here the witch/villain never even appears, the tornado lasts forever, and Dorothy is just continually stuck in the room. Because what Forché’s elegies teach us is that, no matter what kind of Oz we think we’re going to face once the tornado concludes, there is no future beyond the present realities within the tornado outside. And it’s this structural, sequential displacement that I, as a reader, initially found disorienting, but which I eventually settled into as being more reflective of these chaotic times we find ourselves in.

I personally found Forché’s fourth collection Blue Hour to be a bad Zagajewski, or Milosz, impression, like a lecture on Polish mysticism that forgets its own source and embodiment because the class projector won’t work. However, Forché deploys those mystical elements—which have always been present in her work to one degree or another—to staggering effect in her newest collection, as in the close of the poem “A Room” (which also closes the first half of the book): “… as our moments are, ours and the souls of others, who glimmer beside us/ for an instant, here by chance and radiant with significance” (35). She often has poems disappear like mist or sand as they trail off into a distance you can only barely just make out as containing water. The mirage-like quality of many of the poems’ endings have the added benefit of coalescing toward an extremely haunting collective reading experience.

It’s as if Forché is daring the reader to forget the poem, as if the act of remembrance will bring back either the dead or, what amounts to the same, all the lost time spent. As its own sort of Poetry of Witness, it’s concerned with being an antidote to the kind of regimented, meticulous regularity fascistic sentiment thrives on. It is whatever the opposite of watch-obsessed, time-hogging fascistic sentiment can be in poetry—to a world that isn’t taking enough note right now and which can’t be bothered anyway.

Although Forché excels with traditional sequencing and all it can thematically and situationally impute upon a collection (c.f. her great 1994 collection The Angel of History), the two sequences here are even more traditional, even sparser. The second half of the book begins with its most seemingly traditional sequence, entitled “The Ghost of Heaven”, a sequence that gains its power not from its segmentation but more from the way its line breaks elide any sort of boundary otherwise. Its line endings switch freely between parsed line endings and more clean breaks, depending on the demand of the (often short) line. While some of this poem, especially some of the penultimate sections, dips its toes too far into the waters of witness, it brings itself back to a manageable semi-reality with its concluding stanza:

All who come

All who come into the world

All who come into the world are sent.

Open your curtain of spirit. (42)

The situations elide into one another, which would normally create a dangerous precedent; here, however, under the circumstances of this particular collection, the elision reads more like a kind of hard-won grace, often because of and not in spite of the aforementioned line breaks, often in the second part. If the first part introduces the reader to the problems addressed in the collection and elides the borders of what can typically be called a sequence poem, then the second half stays truer to its own forms while opening the internal borders of its poetic techniques even further, as the speaker increasingly retreats into the natural world outside the speaker’s own purview as the collection progresses, getting further away from the self.

In the Lateness of the World contains some of Forché’s most accomplished poetry to date. From the opening salvos to the graceful final poems, the collection rises and falls along measures it controls, and to which each poem alone is attuned to, the forms bending and breaking according to their own strictures. The quasi-sequences of the first half, the contained litanies within “The Refuge of Art” and “A Room”, the way the more traditional sequence “The Ghost of Heaven” juts up against the following more diaristic poems, the way “The End of Something” forms a seemingly simplistic bridge between “A Bridge” and “Early Life”, the prose poetry of “Lost Poem” appearing beside the end-stopped lines of the deceptively dynamic “Charmolypi”, the way the final poems whisk everything away before the penultimate poems “Early Confession” and “Toward the End” reassert the self, and finally the way the closing poem “What Comes” reasserts a mysticism over, above, and through the self—all this attests to Forché’s myriad gifts as a poet, and their continually well-placed deployment makes the collection less of a Greatest Hits collection and more of a Grand Statement. This collection is worth the wait for its bounty of good poetry—a hard-won, hard-fought labor of love.

But she doesn’t perform this act alone—the collection often reads like a refinement of previous collections, or even in some instances an exorcism of the previous demons contained within. I had the benefit of hearing Forché read in 2014, and even though she did read this poem, she couldn’t help remarking on how tired of this poem she was. That poem of course is “The Colonel” from her 1981 collection The Country Between Us, from which her memoir gets its title, based on the opening sentence: “What you have heard is true.” And I can think of no less than two poems in this new collection that attempt to rewrite that very poem on terms where the playing field has levelled out, away from Forché-as-the-speaker’s voice.

The first poem “Museum of Stones” takes the cataloguing impulse in “The Colonel” and flips it on its head, making it stand in for a humanizing impulse rather than a scientific and/or fascistic tendency. The second poem “The Boatman” is the most obvious spiritual sequel to “The Colonel”, taking its cues from that earlier poem, all while inverting the natural progression of the technique and the poem’s objective correlative—all to convey what it’s like to be ferried across the river/roads, in a taxi, as the apocalypse, or something much more natural, occurs in the background.

The fact that Forché opens her new book with a quasi-rewrite of her most famous/infamous poem isn’t cowardly—it is an affirmation of all that poetry can achieve, and all of the human element therein.