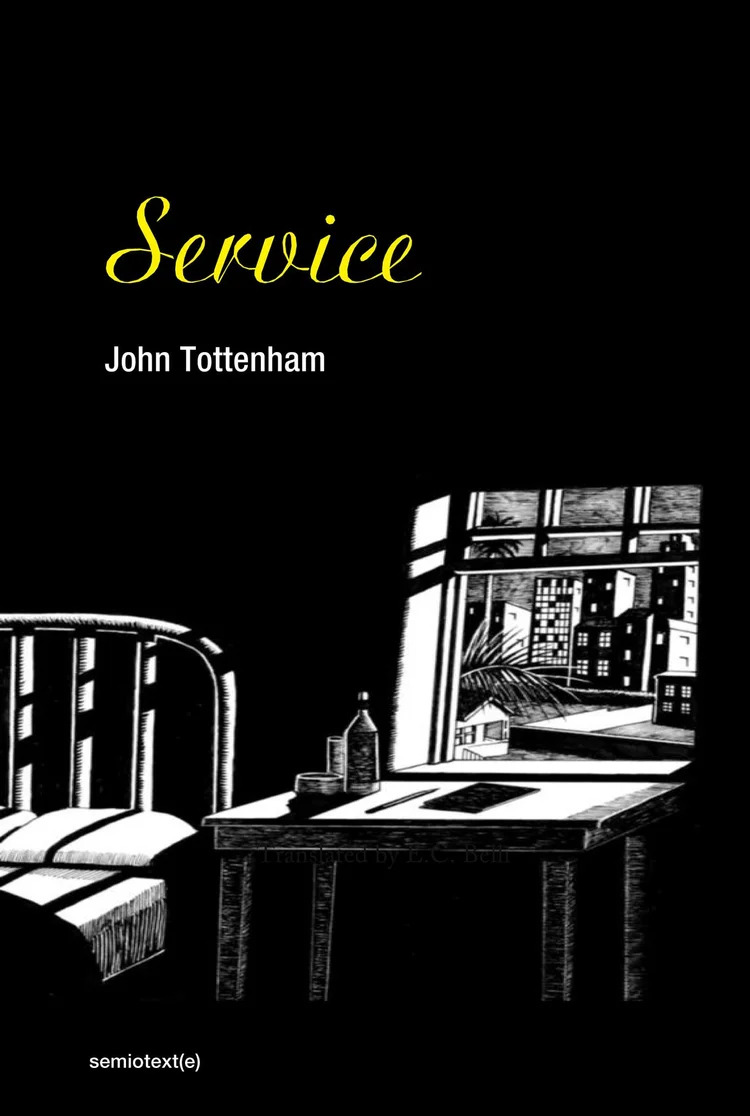

Sean Hangland—the narrator/non-hero of John Tottenham’s hilarious novel of retail horror and art frustration—has had it. His three or four shifts a week at the storied Mute Books on Sunset Boulevard in LA are a trial he can no longer bear. He lashes out at texters, at people who ask where the bathroom is, even at attractive women asking for book recommendations. Once a journalist and aspiring novelist, Sean has lately been reduced to making lists of writers who published multiple books and died younger than he is now. He’s at a breaking point.

Inventorying the many false starts he’s made over the decades, Sean resolves to quit writing for good. The trouble is he can’t think of a single thing he’d rather do. So he calls up his screenwriting pal/drug dealer and scores enough pills to bolster one last heroic campaign at the blank page. All the while, everything from the temptations of the internet to the rapidly-filling trash bag full of collection agency envelopes distract him from his noble task.

Sean spends an inordinate amount of time comparing himself to old friends. Their perceived triumphs in work and love are like albatrosses around his neck. The excuses and explanations the man comes up with to avoid putting pen to paper are as long as they are varied. And yet, he keeps writing.

It’s a rare talent to make hate-filled complaining funny but Tottenham cracks the code again and again. The thing that buoys the book is the self-aware wink implicit on every page. Indeed the writer uses some of the facts of his own biography as a jumping-off point. Tottenham worked at an LA bookstore for decades (he may still, unless the rapturous reviews for this, his first novel, free him of that necessity), but unlike Hangland, he is a celebrated published poet and journalist. He undercuts the tired auto-fiction game by repeatedly using barely-hidden pseudonyms for celebrated writers and musicians throughout. The point is not whether what he writes is factually accurate to the events of his particular biography but that it rings true. There’s rarely a false note over these three-hundred-plus pages.

Just when Sean’s litany of complaints begins to get tiresome, Tottenham undercuts it by introducing a young coworker who becomes an unlikely confidant and trusted editor of Sean’s last-ditch literary effort. The narrative begins to gnaw away at its own tail.

I’ve been working at a bookstore the past few years and trying to get art and books out into the world for decades, so this novel was tailor-made for me. A one-man Black Books, Sean’s complaints about retail indignities made me laugh so hard it hurt.

The very serious question of how to make art in a society that has little use for it whispers quietly beneath the ratcheting-up comedy of Sean’s inevitable Waterloo. After about the dozenth negative Yelp review brought to his attention by Gilbert—his former coworker/now-boss—Sean has the kind of workplace meltdown many of us can only dream of. He is banned from the store he’s been a mainstay at for years and is forced to face his financial and emotional demons face to face.

The trouble is that even if Sean is an angry, pompous, elitist wretch whose comeuppance is well-earned, the problems that plague him cannot be fixed by adopting a sunny disposition or more generous attitude towards colleagues and friends. The question of how to survive, let alone thrive, under the current conditions in this country will not be answered by a novel, no matter how brilliant it may be.

Tottenham makes us laugh as we sink into the mire.