David Foster Wallace’s iconic 90s novel, Infinite Jest, describes a film that is perfect entertainment, so engrossing that viewers can’t look away. Anyone who begins to watch the film becomes sucked in and, without intervention, will continue to watch the film until they die.

I experienced something equally glum over the course of the 2016 election cycle. After following the media narrative closely for nearly two years—all the stories, the punditry, the SNL sketches—I had finally seen through the veil. All the data in the world couldn’t prevent a Trump presidency. And so on November 7th, I fully expected my phone to die. I was flipping through Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, all inundated with election coverage and the attendant shock and rage, without inhibition. My phone was hot metal, the battery was draining, and I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t receiving cancer from the saturation of wireless signals in my palm. I couldn’t look away, and at the same time, I was willing my phone to death. Either it would shut off, or I would. After a point, there’s only so much media one millennial can handle. After a point, every piece of news is just subsumed into the echo chamber. A hollow reality washed over me.

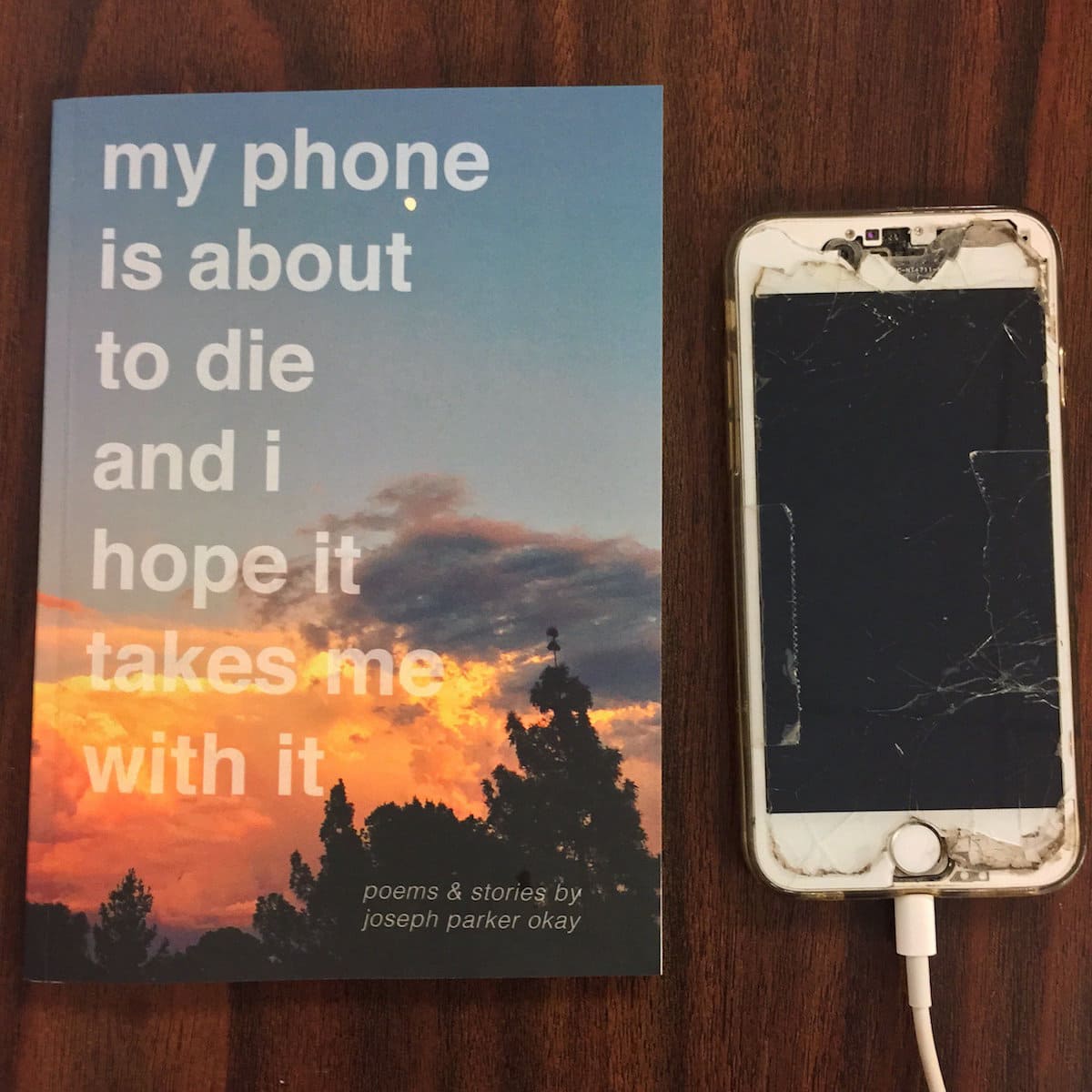

Joseph Parker Okay gets this. He understands why the events of the past year are so horrifying, and paradoxically—as David Foster Wallace himself knew—so funny. The kind “laugh so you don’t cry” funny. My Phone Is About to Die & I Hope It Takes Me With It vents these frustrations via Okay’s darkly subversive verse. The diverse collection, both poetry and short stories, digs at the uncomfortable truths we know and fail to admit, and drags them, kicking and swearing, into something like daylight.

Behind Okay’s dark humor is an even darker ontology: a sense that the world is nonsensical at best, and sinister at worst. Call it depression, call it clarity—regardless, it’s clear that Okay tolerates no bullshit. This frank approach to the real is on display in the collection’s eponymous poem: “your phone is about to die and you hope it takes you with it pt. 1” (22). The opening lines offer a single, bleak observation: that life is shot through with shittiness:

you’re sick of taking shitty phone calls from shitty people so you

put your shitty head through your shitty computer monitor

This couplet rings of hyperbole, but actually approaches something close to truth. After all, the memes we frequently share, though hyperbole themselves, do encapsulate real human feeling; this is why we relate to them, and exchange them like language. We laugh at the notion of putting our heads through computer monitors, we think we’d never do such in a thing. And yet, in an overtly shitty reality, smashing one’s head through a computer monitor doesn’t seem such a bad way to go.

In Okay’s world, every observation reveals an irony, a nasty joke, a hidden threat. One tiny poem, “what even is the sky,” offers a single bleak admission: “why does it make me / so nervous (25). The cosmos itself is playing pranks, as in another poem, “is the universe expanding to scale?” This poem subverts the orientation of its own question with its first line: “or is everything constantly being skewed?” (26). This is a world that has a cruel sense of humor, and Okay’s wry observations are all that stand in the way of despair, if despair has not already set in. There’s a reason that the titles of so many of Okay’s poems bleed into single-phrase responses: there’s little more to be said.

Consider this one-line zinger, “the sun destroys everything eventually”:

i’m patiently waiting my turn

This is a hilarious little poem. The build up is a parody of fatalism, and the payoff is delightfully underwhelming, if not also deeply tragic.

Okay is not above offering a few snatches of hope. “i’m trying to enjoy life even though i don’t understand it” is a half-hearted attempt to make the best of things, describing a state of mind beyond sadness (45):

most days i don’t think i’m feeling sad

i think i’m just feeling the way things are

The best case scenario for Okay is not the presence of joy, but the absence of sadness. Okay’s answer to this un-sad feeling? To watch a video on Vine. Technology, specifically the hyperbole of the Internet, is the coping mechanism Okay needs to survive. Of course, when this too is proven hollow, he’s back to wishing his phone would explode.

Okay’s short stories echo the themes present in his poetry. “dog waste attracts and feeds rats” describes two women who don’t know how to be happy, and touches on the inability of art to bridge the distance between people. “i don’t like seeing myself through a subjective lens that’s not my own,” one says to another, but her partner is already reimagining an earlier scene, and preparing to commit it to writing. Another short piece, “the empty space inside will always get a little emptier” describes a drinking problem juxtaposed with the narrator’s dependency on “the void,” a relational conglomerate that “doesn’t owe me anything” subjects him to “more emotional anguish than i knew i could bear” (76). Even relationships in Okay’s work are disappointing, fraught with danger, and best left alone.

In spite of all this pessimism, My Phone Is About to Die does evoke empathy. Okay’s poetry and taught fiction reach out to the reader, begging them to see what he sees, to admit that reality is neither clean nor clear, but sordid and dark with personal bitterness, apathy, abusive power, and—if we were to apply religious language—sin. And yet as collection of formal literature, My Phone Is About to Die inverts its own subject matter. Okay’s content is lonesome, and yet the literary forms he marshals around his ideas implies that this content is meant to be shared. At its best, My Phone Is About to Die is an invitation to confront the poor relationships, rotten systems, and sold-out media of our time, and to do so not alone, but as readers. And as readers, we are never really alone.

In his afterward, Okay promises that “bad things will continue to happen in my life and i’ll continue to write about them.” Closure be damned, if not expected. And yet there is something inherently therapeutic, something which, I trust, Okay does not fail to see: in writing the words themselves, there may be hope. In wishing for a phone to die, there may be a reason to live.